Table of Contents

Passage

A William Curry is a serious, sober climate scientist, not an art critic. But he has spent a lot of time perusing Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s famous painting “George Washington Crossing the Delaware,” which depicts a boatload of colonial American soldiers making their way to attack English and Hessian troops the day after Christmas in 1776. “

Most people think these other guys in the boat are rowing, but they are actually pushing the ice away,” says Curry, tapping his finger on a reproduction of the painting. Sure enough, the lead oarsman is bashing the frozen river with his boot. “I grew up in Philadelphia. The place in this painting is 30 minutes away by car. I can tell you, this kind of thing just doesn’t happen anymore.”

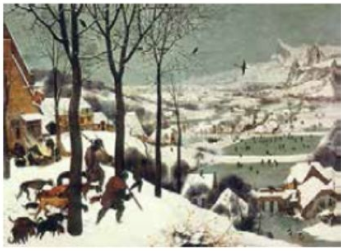

B. But it may again soon. And ice-choked scenes, similar to those immortalized by the 16th-century Flemish painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder, may also return to Europe. His works, including the 1565 masterpiece “Hunters in the Snow,” make the now-temperate European landscapes look more like Lapland. Such frigid settings were commonplace during a period dating roughly from 1300 to 1850 because much of North America and Europe was in the throes of a little ice age.

And now there is mounting evidence that the chill could return. A growing number of scientists believe conditions are ripe for another prolonged cooldown, or small ice age. While no one is predicting a brutal ice sheet like the one that covered the Northern Hemisphere with glacier about 12,000 years ago, the next cooling trend could drop average temperatures 5 degrees Fahrenheit over much of the United States and 10 degrees in the Northeast, northern Europe, and northern Asia.

C. “It could happen in 10 years,” says Tenence Joyce, who cha ừ s the Woods Hole Physical Oceanography Department. “Once it does, it can take hundreds of years to reverse.” And he is alarmed that Americans have yet to take the threat seriously.

D. A drop of 5 to 10 degrees entails much more than simply bumping up the thermostat and carrying on. Both economically and ecologically, such quick, persistent chilling could have devastating consequences. A 2002 report titled “Abrupt Climate Change: Inevitable Surprises,” produced by the National Academy of Sciences, pegged the cost from agricultural losses alone at $100 billion to $250 billion while also predicting that damage to ecologies could be vast and incalculable. A grim sampler: disappearing forests, increased housing expenses, dwindling freshwater, lower crop fields and accelerated species extinctions.

E. Political changes since the last ice age could make survival far more difficult for the world’s poor. During previous cooling periods, whole tribes simply picked up and moved south, but that option doesn’t work in the modem, tense world of closed borders. “To the extent that abrupt climate change may cause rapid and extensive changes of fortune for those who live off the land, the inability to migrate may remove one of the major safety nets for distressed people,” says the report.

F. But first things first. Isn’t the earth actually warming? Indeed it is, says Joyce. In his cluttered office, full of soft light from the foggy Cape Cod morning, he explains how such warming could actually be the surprising culprit of the next mini-ice age. The paradox is a result of the appearance over the past 30 years in the North Atlantic of huge rivers of freshwater the equivalent of a 10-foot-thick layer mixed into the salty sea. No one is certain where the fresh torrents are coming from, but a prime suspect is meltin ị Arctic ice, caused by a buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that traps solar energy.

G. The freshwater trend is major news in ocean-science circles. Bob Dickson, a British oceanographer who sounded an alarm at a February conference in Honolulu, has termed the drop in salinity and temperature in the Labrador Sea— a body of water between northeastern Canada and Greenland that adjoins the Atlantic—”arguably the largest full-depth changes observed in the modem instrumental oceanographic record.” could cause a little ice age by subverting the northern.

H. The trend penetration of Gulf Stream waters. Normally, the Gulf Stream, laden with heat soaked up in the tropics, meanders up the east coasts of the United States and Canada. As it flows northward, the stream surrenders heat to the an. Because the prevailing North Atlantic winds blow eastward, a lot of the heat wafts to Europe.

That’s why many scientists believe winter temperatures on the Continent are as much as 36 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than those in North America at the same latitude. Frigid Boston, for example, lies at almost precisely the same latitude as balmy Rome. And some scientists say the heat also warms Americans and Canadians. “It’s a real mistake to think of this solely as a European phenomenon,” says Joyce.

I. Having given up its heat to the air, the now-cooler water becomes denser and sinks into the North Atlantic by a mile or more in a process oceanographers call thermohaline circulation. This massive column of cascading cold is the main engine powering a deepwater current called the Great Ocean Conveyor that snakes through all the world’s oceans. But as the North Atlantic fills with freshwater, it grows less dense, making the waters carried northward by the Gulf Stream less able to sink.

The new mass of relatively freshwater sits on top of the ocean like a big thermal blanket, threatening the thermohaline circulation. That in turn could make the Gulf Stream slow or veer southward. At some point, the whole system could simply shut down, and do so quickly. “There is increasing evidence that we are getting closer to a transition point, from which we can jump to a new state. Small changes, such as a couple of years of heavy precipitation or melting ice at high latitudes, could yield a big response,” says Joyce.

J. “You have all this freshwater sitting at high latitudes, and it can literally take hundreds of years to get rid of it,” Joyce says. So while the globe as a whole gets warmer by tiny fractions of 1 degree Fahrenheit annually, the North Atlantic region could, in a decade, get up to 10 degrees colder. What worries researchers at Woods Hole is that history is on the side of rapid shutdown. They know it has happened before.

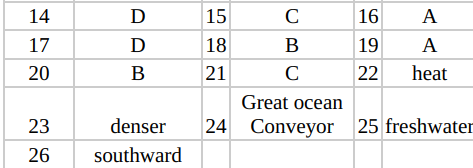

Questions

Question 14-16

Choose the correct letter, A, B, c or D.

Write the correct letter in box 14-16 on your answer sheet.

14 The writer mentions the paintings in the first two paragraphs to illustrate

A that the two paintings are immortalized.

B people’s different opinions.

C a possible climate change happened 12,000 years ago.

D the possibility of a small ice age in the future.

15 Why is it hard for the poor to survive the next cooling period?

A because people can’t remove themselves from the major safety nets.

B because politicians are voting against the movement,

C because migration seems impossible for the reason of closed borders.

D because climate changes accelerate the process of moving southward.

16 Why is the winter temperature in continental Europe higher than that in North America?

A because heat is brought to Europe with the wind flow.

B because the eastward movement of freshwater continues,

C because Boston and Rome are at the same latitude.

D because the ice formation happens in North America.

Questions 17-21

Match each statement (Questions 17-21) with the correct person A-D in the box

below. Write the correct letter A, B, C or D in boxes 17-21 on your answer sheet.

NB: You may use any letter more than once.

17 A quick climate change wreaks great disruption.

18 Most Americans are not prepared for the next cooling period.

19 A case of a change of ocean water is mentioned in a conference.

20 Global warming urges the appearance of the ice age.

21 The temperature will not drop to the same deg

List of People

A Bob Dickson

B Terrence Joyce

C William Curry

D National Academy of Science

Questions 22-26

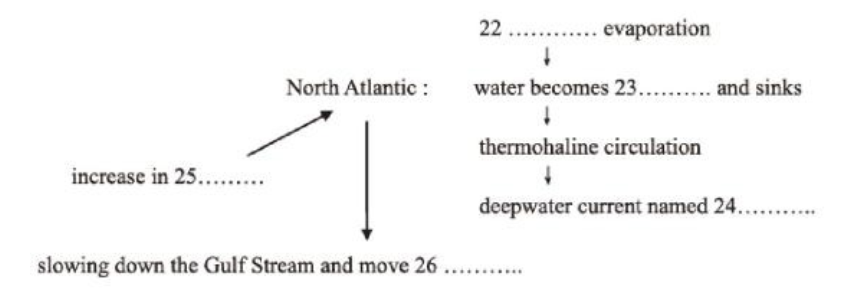

Complete the flow chart below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each

answer. Write your answers in boxes 22-26 on your answer sheet.

Answers